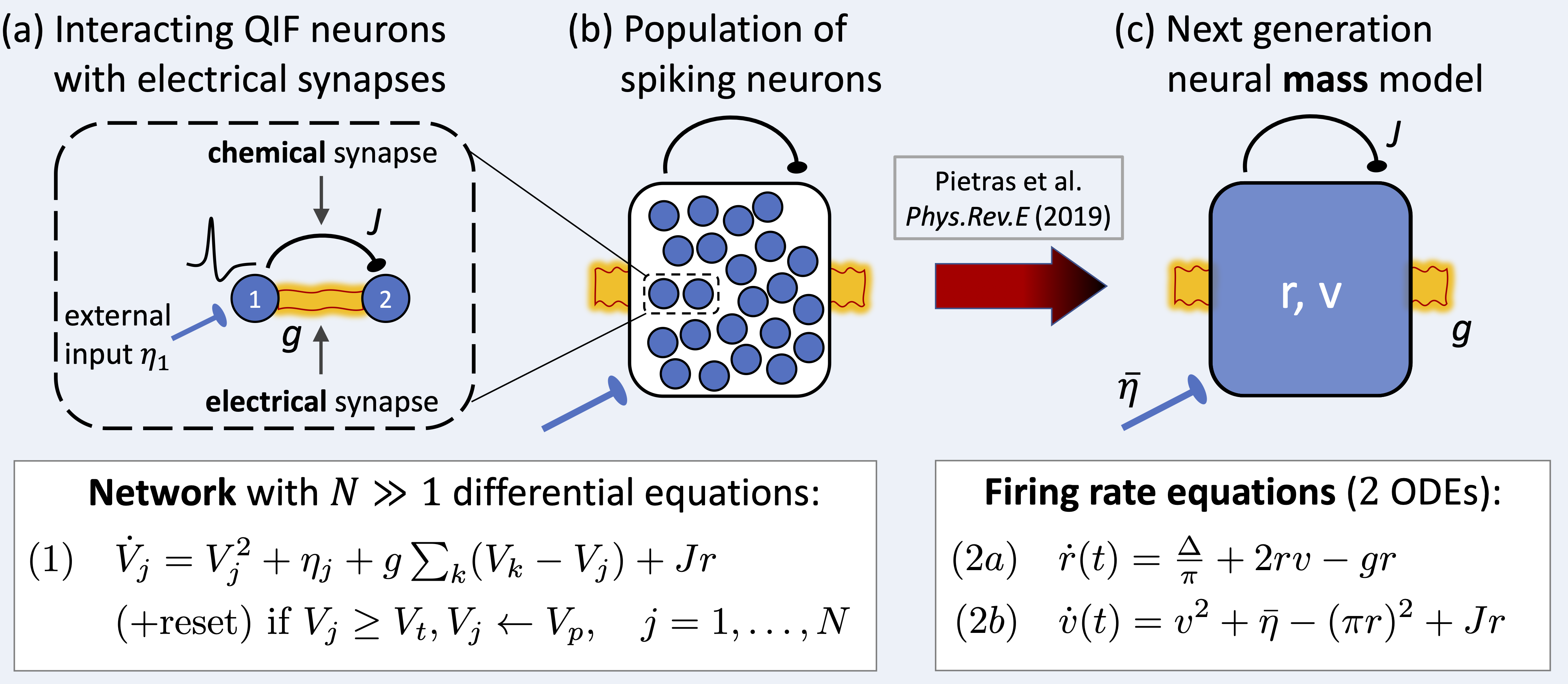

QIF neurons with gap junctions

exact low-dimensional network dynamics

The human brain is probably the most complex system we know. Tremendous efforts and progress in neuroscience research has been made since Hans Berger’s discovery of the alpha rhythm in 1924. But a central question remains unanswered: how do the billions of interacting neurons in our brain generate macroscopic phenomena such as the coherent steering of muscles in locomotion, grasping, pattern recognition, working memory or decision making? Experimental neuroscience has provided ample evidence that these brain functions—and their pathological dysfunction—come along with characteristic neural activity patterns and brain rhythms. Neuronal synchrony is at the heart of perceiving and processing information as well as exchanging it across brain regions, which requires a careful balance of excitation (E) and inhibition (I). Disturbing the E-I balance can critically alter communication pathways and lead to, e.g., excessive beta-band oscillations in Parkinson’s disease or spatially propagating epileptic seizures in form of traveling waves. An increasing number of recent experimental findings point out that electrical synapses are ubiquitous across brain regions and species. Electrical synapses are broadly present between inhibitory neurons and widely believed to promote synchrony. They are therefore immediately implicated in the generation of brain rhythms, they directly affect the E-I balance and are thus critical for the functioning of our brain. But their overall functional role remains elusive, and how exactly they interact with inhibitory synapses to generate oscillations is unknown.

Traditionally, firing rate models have been proposed to describe the collective dynamics of large populations of neurons and to obtain a mechanistic understanding of neural computations. But traditional mean-field theories, besides other major limitations, are incompatible with electrical synapses. Towards developing a mean-field theory that can incoporate gap junctions, a novel approach has recently been proposed by Ernest Montbrió, Diego Pazó, and Alex Roxin, which is related to the Ott-Antonsen ansatz for coupled oscillators. They showed by a unique example of exact mean-field reduction how to link the microscopic dynamics of quadratic integrate-and-fire (QIF) spiking neurons to an exact macroscopic mean-field description. The resulting firing-rate model, which has been coined “next-generation neural mass model” is (1) exactly derived from a network of spiking neurons and (2) accurately describes, both qualitatively and quantitatively, any collective state of the neuronal network, including synchronous states and transients. It is low-dimensional, has a simple mathematical form, and is thus amenable to analysis, which allows for a thorough exploration of the dynamics and a full understanding of the underlying computational principles. Very recently, we advanced the novel mean-field theory by successfully deriving an exact next-generation neural mass model for spiking neurons with mixed chemical and (3) electrical synapses. The development of such an exact mean-field description incorporating electrical synapses was urgently needed, given the ubiquity of electrical synapses in the brain, and it presents the first step towards a mean-field theory for spiking neuron networks with electrical synapses.